This week, the Government announced its proposed regulatory design for the long-awaited offshore renewable energy regime. The announcement was one of a suite of energy-related announcements released as part of the Government's Electrify NZ plan.

The regime is intended to cover all commercial offshore renewable energy infrastructure up to and including the exclusive economic zone, including wind, solar, wave, tidal, and offshore transmission infrastructure. However, the Government has recognised that offshore wind is the most mature technology and that offshore wind projects will likely be the first projects ready for permit applications.

The Bill to enact the offshore renewable energy regime is expected to be introduced by the end of 2024 and passed in mid-2025, with the first feasibility permit round initiated by late 2025 and the first permits granted in 2026. Consultation on the Bill will take place during the select committee process, once the Bill has passed its first reading – this is expected to be between January and June 2025.

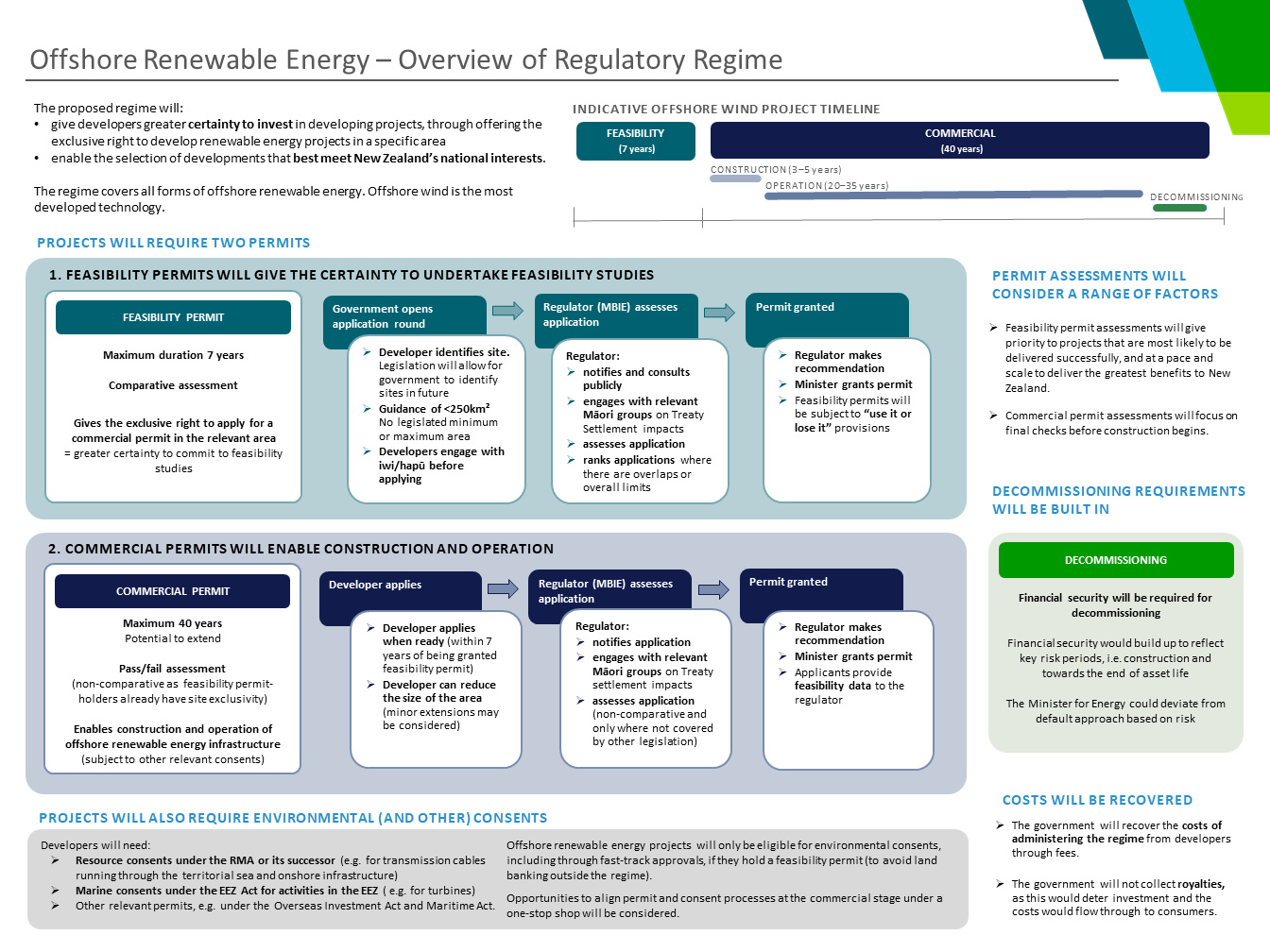

In the meantime, the key design features of the proposed regulatory framework are as follows:

1) The Government is moving at pace to establish a credible permitting regime for offshore renewable energy, by aligning its regime with other existing regimes.

The design of the permitting regime purports to “borrow the best” from more mature regimes in the United Kingdom, Netherlands, Denmark and Australia and adapt it to New Zealand’s settings.

The Government has indicated that a key driver of the short timeline for passing legislation and launching the offshore renewable energy regime is to allow developers to align activities and supply chains with Australia. Many of the regime's features (as noted below) align with the Australian framework, which will be welcome news for developers planning or undertaking projects in Australia who might also consider offshore wind in New Zealand.

As discussed in our March 2023 Energy Blog, it is important that New Zealand moves quickly and establishes a credible and easy to use permitting regime for the development of offshore renewable energy facilities. By aligning many aspects of our regime with Australia, there are time and cost savings to design and implement the regime. For similar reasons, parts of the regime, including regulatory powers, functions and enforcement tools, will align with the permitting regime for petroleum and minerals under the Crown Minerals Act 1991 (CMA).

2) Two permit regime, with 'use it or lose it' provisions to address the risk of seabed banking.

Feasibility permits will provide the holder the exclusive right to apply for a commercial permit for a specified area. Feasibility permits will:

- not have a legislated maximum area, but rather "cover a single contiguous area that is reasonable for the proposed development". The Government suggests that this is likely to be around 250km for 1GW developments, but we expect further clarity will be available when the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) issues further guidance.

- be issued for up to seven years, with extensions able to be granted by the Minister for Energy in limited circumstances. The Minister may revoke the permit if the holder does not begin feasibility activities within 12 months or meet milestones without reasonable justification (eg supply chain constraints). The 'use it or lose it' provisions are intended to ensure that good sites are not locked up without satisfactory progression of development activities.

- in exchange for exclusivity, require the permit holder to disclose non-commercially sensitive feasibility data acquired when the permit expires, or a commercial permit is awarded, such as environmental surveys and baseline studies.

Commercial permits will enable the building and operating of offshore renewable energy infrastructure and will be required before construction can begin. They may be sought at any time within the seven-year duration of the feasibility permit and will be awarded following an application from the feasibility permit holder and an independent, non-comparative assessment. Commercial permits will have an initial duration of up to 40 years, with the ability to be extended up to a further 40 years (with approval) if appropriate to accommodate the full operational life of an asset. The 40 years duration is consistent with both the CMA and the Australian regime.

The regulator may impose conditions on both types of permits, which we expect will largely align with those available to be imposed under the CMA. Such conditions could include adhering to the project design or work programme, timely fee payment, providing information or reports on the regulator's request, and disclosing feasibility data.

3) The allocation rounds and comparative assessment for awarding feasibility permits will drive competition for optimal project sites.

The Government is focussed on enabling projects that are most likely to deliver the greatest benefits for New Zealand. Feasibility permits will be allocated in application rounds following a comparative, merits-based assessment, and each round may be limited by generation capacity, spatial area or technology type. Under the developer-led approach, developers will be responsible for identifying and applying for sites, however, the Government will have the ability to select sites where appropriate. Where there is an overlap between developers for proposed permit areas, the regulator may invite applicants to nominate another area. We expect this to drive competition between developers for optimal sites and that investors will want to act quickly to secure feasibility permits.

The Minister for Energy will primarily consider energy system benefits and technical and financial capability of projects when deciding whether to award feasibility permits. Other considerations at the feasibility permit stage include wider economic benefits, decommissioning arrangements, compliance records, iwi and hapū engagement, management of existing rights, interests and limitations, and national security or public order risks.

Commercial permit applications will be assessed once the developer is ready following feasibility studies, and not as part of a comparative round. Assessment of commercial permits will be based on a smaller subset of the feasibility permit considerations, primarily whether construction is ready to begin and relevant risks are managed.

4) Only holders of feasibility permits will be able to obtain resource or marine consents for offshore renewable energy infrastructure.

Developers will need resource and/or marine consents for the construction and operation of offshore renewable energy infrastructure under the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) (or its successor, noting the RMA is currently under review) and the Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf (Environmental Effects) Act 2012 (EEZ Act). However, developers must hold a feasibility permit before they can apply for such resource and/or marine consents.

The Government now intends to amend the Fast-track Approvals regime, RMA (or its successor) and EEZ Act once the offshore renewable energy regulatory regime is in force, to allow applications for marine and resource consents for offshore renewable energy projects to be eligible for the fast-track approvals process.

Other relevant permits may also be required under the Overseas Investment Act 2005 (OIA) and Maritime Transport Act 1994. We do not consider that securing OIA approval will be a barrier for credible international investors, due to the likely scale of job creation and associated regional economic development, and general benefits to New Zealand's energy system and carbon reduction and energy transition aims.

5) Competing uses will require strategic marine environment planning.

Under the developer-led approach, the grant of a feasibility permit will not prevent other authorised offshore activities (such as mining or aquaculture) from acquiring environmental consents within the permit area. This could potentially exclude offshore renewable energy developments from being consented, where competing users cannot co-exist. However, given some of these competing uses are or will be regulated by the Crown, the Crown may seek to resolve overlaps through a level of strategic planning in the marine environment.

6) Early identification of Treaty issues and close partnership with iwi and hapū will be important.

Developers applying for permits will be required to identify relevant rights stemming from Treaty settlements and consult relevant iwi, hapū or Māori groups on the proposed development/permit application before applying for permits. Developers will need to engage with Māori from the beginning of the process, which will be crucial to ensure that sufficient consultation is undertaken.

We anticipate that investors may also consider the role that iwi and hapū can play as co-investors, partners and contributors to offshore renewable energy projects, given the projects' long life cycle, connection to the moana, and ability to provide jobs and opportunities.

7) Decommissioning requirements and trailing liability will be backed by financial accountability.

Permit holders will be required to decommission infrastructure, provide a decommissioning plan to the regulator and Environmental Protection Authority, and provide a cost estimate to the regulator based on the cost of fully removing infrastructure. Permit holders will also be required to obtain and maintain one or more financial securities to enable the Crown to recover decommissioning costs in the event of permit holder's default.

The form and amount of financial security will be determined by the Minister based on the cost estimate and will reflect the risk profile of the developer and the nature of the project. This is expected to largely align with the decommissioning obligations in the CMA and the Australian regime.

The Government also intends to introduce trailing liability provisions for the decommissioning of infrastructure or the maintenance of financial security, which may be removed or maintained at the Minister's discretion. The final design of the trailing liability provisions will be included in the legislation, but the Government has indicated that these will allow less flexibility on the kind and amount of financial security a permit holder must provide than the CMA. However, this is balanced out by the greater discretion given to the Minister regarding the imposition of trailing liability than the CMA.

8) The regime will enable safety zones.

Safety zones of up to 500 metres will be able to be established around offshore renewable energy infrastructure, in order to prohibit unauthorised persons or vessels from entering the area. This aligns with the Australian approach.

9) No royalties, but no price support.

The cost of administering the proposed regime will be funded by fees paid by developers. The Government considers that revenue-gathering mechanisms such as royalty schemes would deter investment and the costs would flow on to consumers. This differs from the approach taken under the CMA, but aligns New Zealand's approach with the Australian regime, which does not include royalties.

The Government has also signalled that it is not intending to offer any price support. This is despite most offshore wind projects internationally having been supported by some form of government-backed price support mechanism. The Government considered that such a mechanism would be a material departure from the market-based electricity model in New Zealand.

10) The responsibility for offshore transmission infrastructure will consist of a hybrid model between permit holders and Transpower.

The Government's in-principle approach to offshore transmission infrastructure involves:

- commercial permit-holders being responsible for planning, building and funding new offshore transmission infrastructure; and

- Transpower being responsible for owning, operating and decommissioning the offshore transmission infrastructure and prescribing technical design standards.

Developers may also contract with Transpower to plan and build the offshore transmission infrastructure. The Government intends to engage in more policy development to flesh out the details of offshore transmission infrastructure regulation, which we will continue to monitor.

Next steps

You can find the Government's overview of the offshore regulatory regime on MBIE's website here (and also see MBIE's plan included below).

We expect that the Bill to enact the regime will be introduced into Parliament by the end of 2024, with select committee consultation anticipated to take place between January and June 2025.

If you would like to discuss the implications of the proposed regime, please get in touch with one of our experts below.