View infographic pdf here.

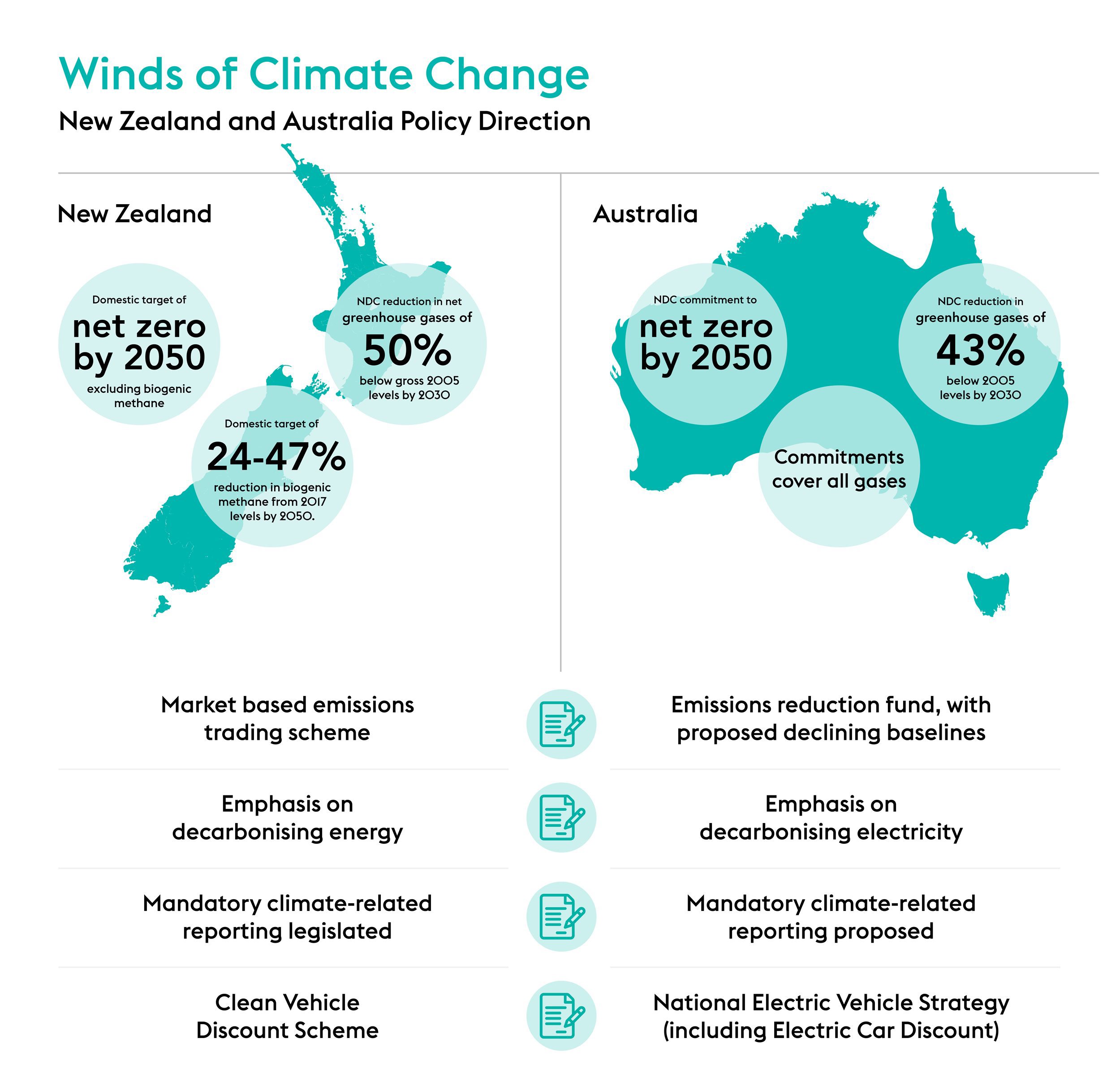

Following an election campaign dominated by climate and cost of living issues, the recent election of the Hon Anthony Albanese MP's Labour Party to govern Australia has been heralded by many as a new dawn for climate action on the other side of the Tasman. Last month, the Australian Prime Minister communicated an updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the United Nations under the Paris Agreement, along with a range of proposed policy reforms.

In this update, we summarise some of the key aspects of those proposed reforms and compare those with the New Zealand Government's approach to climate change following the release of the first emissions reduction plan (ERP) in May of this year. While a change of government in Australia may create new risks in some industries, it also presents new opportunities, particularly where organisations can capitalise on the alignment of pro-climate policy across jurisdictions.

What are the key changes to climate policy in Australia following the election?

On 16 June, the Australian Government conveyed Australia's updated NDC to the Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Australia's updated NDC:

- commits to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 43% below 2005 levels by 2030 (an improvement from its prior commitment of a 26-28% decrease); and

- confirms Australia's commitment to net zero emissions by 2050.

The latter target had been set domestically by Scott Morrison's government, but not included in an updated NDC. Under the previous government, the approach to achieving that target was set out in its Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan, published in late 2021. Its cornerstone principle was "technology not taxes", and as such the plan focused on actions such as driving down costs for new technologies such as clean hydrogen, low cost solar and carbon capture and storage, while remaining committed to protecting Australia's traditional export industries.

Given Anthony Albanese campaigned on being more ambitious than Scott Morrison on climate, it is unsurprising that his government has now committed to a range of policy proposals in line with its 2021 "Powering Australia" plan. These include:

- A $20bn investment in the electricity grid so that it can handle more renewable power. This will be complemented by an additional $300m for community batteries and solar banks.

- $3bn from the National Reconstruction Fund to support renewables manufacturing and the deployment of low emissions technologies.

- A Powering the Regions Fund, which is intended to support the development of clean energy industries (eg hydrogen) and decarbonisation of existing industries.

- The introduction of declining emissions baselines for major emitters under the "Safeguard Mechanism", which is a key pillar of Australia's Emissions Reduction Fund.

- A National Electric Vehicle Strategy, which is intended to accelerate the uptake of electric vehicles.

- The introduction of mandatory climate-related disclosures for large businesses.

- A commitment to reduce the emissions of Government agencies to net zero by 2030.

- The restoration of the role of Climate Change Authority as an independent source of advice to the government on a wide range of matters relating to climate change.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the outcome of the Australian "climate election" in 2019 (which Labour lost at least in part due to its failure to reach coal communities), the Albanese policies announced to date do not propose to significantly impact traditional industries such as fossil fuels. This is likely to disappoint climate activists and it will be interesting to see whether the new government attempts, or is politically able to, advance a more ambitious agenda over the coming three years.

How do Australia's new proposed policies compare with New Zealand's policy outlook?

To some extent, the key differences between the policies announced by the Australian government and those enshrined in New Zealand's ERP reflect differences in the natural resources and infrastructure profiles of each country. For example, Australia's investment in decarbonising its electricity grid reflects the comparatively low levels of renewable generation in Australia's grid at present (around 24% of Australia's grid was renewable in 2020) and natural factors such as the abundance of solar energy to be harnessed. By comparison, New Zealand's electricity grid is highly renewable, and the ERP accordingly prioritises decarbonisation across the energy sector more broadly (although the "aspirational" target of 100% renewable electricity by 2030 remains, at least formally, in place).

Other differences are more political. Australia's Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF), its primary emissions reduction tool, operates quite differently to New Zealand's emissions trading scheme (ETS). The ERF is a voluntary scheme whereby participants are rewarded with credit units for undertaking certain emissions reduction projects – these credits can then be sold to the government or in the secondary market. The "safeguard mechanism" places an emissions limit (or "baseline") on the largest emitters, although those emitters can surrender carbon credits to offset any emissions over the baseline. The ERF reflects a fraught political history in Australia – the Gillard government had introduced a more comprehensive carbon pricing scheme in 2011 but this was repealed by the Liberal-National government in 2014 and replaced with the ERF. In the years since, the ERF has been criticised for failing to sufficiently incentivise emissions reduction and for issuing credits which do not represent genuine emissions cuts. This has led to the new government proposing declining baselines and announcing an independent review into the carbon credit system.

Many of the Australian government's proposals, however, also resonate with similar policies already adopted or proposed in Aotearoa. For example:

Transport

Australia's proposed National Electric Vehicle Strategy will include an Electric Car Discount, which will offer tax concessions for non-luxury energy efficient vehicles. It is expected that the strategy will also include other proposals to increase the proportion of electric vehicles on Australia's roads. By comparison, the ERP identifies accelerating the uptake of low-emission vehicles as a key action, including by continuing the Clean Vehicle Discount scheme, considering the future of the Road User Charge exemption for light vehicles beyond 2024, increasing access to EVs for low-income households and improving charging infrastructure. Importantly, however, the promotion of electric vehicles in the ERP sits alongside actions designed to reduce reliance on private vehicles and encourage walking, cycling and the use of public transport. In Australia, many similar policies will sit at the state level rather than being managed through national government direction.

Mandatory reporting

The Australian government proposes to introduce mandatory climate-related reporting, in line with international standards, for large businesses. This proposal would bring Australia broadly into line with New Zealand, which is an early adopter of mandatory climate risk reporting in line with the recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). Whether or not a formal disclosure regime emerges in Australia, the continued trend towards climate-related disclosures presents both a risk and an opportunity for impacted businesses. Organisations that prepare high-quality reporting and can demonstrate their climate resilience will be well-placed to attract investment in circumstances where investors are increasingly concerned with ESG risks. On the risk side, organisations who fail to adequately report face both market and litigation risk, and it is therefore critical that organisations working across jurisdictions ensure their reporting meets all relevant legislative requirements and regulatory expectations. Helpfully, the External Reporting Board is aiming to develop New Zealand's climate disclosure framework broadly in line with international precedents (including TCFD and prototype standards issued by the International Sustainability Standards Board), and we are hopeful that approach will minimise the risk (and maximise the opportunity) arising from reporting in dual jurisdictions.

Decarbonising industry

Australia's "Powering the Regions Fund", which will be backed by funding from the ERF and the Climate Solutions Fund, prioritises:

- supporting industry with its decarbonisation priorities (such as energy efficiency improvements and fuel switching);

- the development of new clean energy industries (such as green hydrogen and bioenergy); and

- workforce development.

The Government has also prioritised the development and deployment of zero emissions technology by, for example, partnering with the United States in a "Net-zero technology Acceleration Partnership".

Similar policies can be seen in New Zealand's ERP. For example, these policies include:

- supporting industry to improve energy efficiency, reduce costs and switch from fossil fuels to low-emissions alternatives through the Government Investment in Decarbonising Industry fund and the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority's business programmes;

- investigating low-emissions energy supply options for renewable gas and bioenergy to support future emissions reduction;

- developing a roadmap for hydrogen in Aotearoa by 2023, and ensuring regulatory settings for hydrogen are fit for purpose; and

- plans to support workforce transition in a number of sectors.

While the focus on decarbonising industry undoubtedly creates risks for traditional industry, the convergence of approaches between Australia and New Zealand may well present opportunities for businesses operating across jurisdictions. For example, businesses may wish to seek economies of scale by considering fuel switching opportunities across both jurisdictions simultaneously. Similarly, the focus on the development of new industries in both countries simultaneously could converge opportunities for investors in new technology projects.

Net zero governments

Last year, the New Zealand government launched the Carbon Neutral Government Programme, which aims for a number of public sector agencies to achieve carbon neutrality by 2025. The Australian government has now set itself a similar goal (but with a target year of 2030).

What are the significant gaps that remain between climate policy in New Zealand and Australia?

Despite the election of Labour in Australia resulting in greater convergence of policies with New Zealand, there remain a number of "gaps".

To take just a few significant examples:

- Emissions pricing: As already noted, Australia does not have a fully-fledged emissions trading scheme, and the new government's proposal to introduce declining baselines under the Safeguard Mechanism does not go as far as to introduce one. This is a significant divergence from New Zealand's approach to climate change. In Aotearoa, the ETS is the primary tool for climate change mitigation and, indeed, some commentators have suggested it is the only tool necessary to achieve our climate goals. Without a comprehensive emissions pricing regime, Australia risks facing continued criticism from the international community that it is failing to undertake sufficient mitigation (although aspects of New Zealand's ETS, such as the exclusion of agriculture, have also been criticised). On the other hand, the comparatively lower compliance costs are likely to be seen as a benefit of operating in Australia for many traditional industries (although moves in the EU and other jurisdictions to curb "emissions leakage", whereby high emitting industries move to jurisdictions with lower compliance costs, may limit Australia's economic potential in that regard).

- Oil and gas exploration: New Zealand banned all new offshore oil and gas exploration permits in 2018. Australia has announced no such policy. Indeed, the export of fossil fuels (particularly LNG and coal) remains a key industry for the Australian economy and Labour has indicated that it supports continued investment in new fossil fuel infrastructure.

- Agricultural emissions: The Australian government has to date provided little in the way of policy direction for the agricultural sector, although it has signalled a focus on the development and commercialisation of emissions-reducing livestock feed and improving carbon farming opportunities. By comparison, the He Waka Eke Noa partnership between government and the primary sector in New Zealand recently released a set of recommendations for pricing agricultural emissions as an alternative to bringing agriculture into the ETS. The Government will consider these recommendations, alongside advice from the Climate Change Commission, and will make a decision by the end of this year on how agricultural emissions should be priced. The default position, if the He Waka Eke Noa partnership does not achieve sufficient progress, is that agricultural emissions will be brought into the ETS by 2025.

These gaps likely reflect a range of factors including Australia's recent history of conservative government, Australia's constitutional makeup (with many climate-related matters left to individual states and territories), the traditional industries that have formed the backbone of Australia's economy, and the recent progress New Zealand has made through the release of the first ERP. In our view, while New Zealand is arguably further ahead in its policy support for emissions reduction initiatives, meeting 2050 net zero targets remains a challenging proposition for both countries. Organisations in both countries should remain prepared to engage with government on the detail of relevant policy reforms as both countries move from a "target setting" phase to implementing specific emissions reduction proposals.